Are old lenses as good as new ones?

Just how good are older lenses? Can you use old models, or do you have to have the latest to be sure of getting good pictures?

By Peter Hennig

Are old lenses as good as new ones? Just how good are older lenses? Can you use old models, or do you have to have the latest to be sure of getting good pictures?

By Peter Hennig If you go out today and buy a cheap camera, it may even come with such refinements as a built-in flash. This is an expensive element in the camera's construction as a proportion of its final, low price, but if you take a closer look at the lens you will see where all the money was saved. The thing that is going to produce the actual picture is a little piece of glass consisting of two lens elements cemented together in front of a very simple shutter. In all essentials it is a Chevalier Achromat of 1835, a design that today can be produced in large quantities for a very low price.

Leica II with Elmar 3.5/50 from the 1930's. A good combination even in 1998.

An 1835 design today

What used to be an annoyingly low maximum aperture can be compensated for by the high-speed films to which we now have access, and other significant optical errors may be lessened by using a curved film path. Anti-reflection coating is not needed for a lens that only consists of a single element, and this again helps keep production costs down. It may come as a bit of a shock that cameras sold today are equipped with lenses of a design that dates back to the early nineteenth century, but in practice the results are perfectly adequate - the pictures serve well enough as unpretentious souvenirs.

As it turns out that the new camera we bought was not as new as we thought, it is worth taking a look at more advanced lens designs of the past to see how well they hold up.

Earlier high quality lenses

When you look at pictures taken at the turn of the century you may often be surprised by the high quality: the sharpness and reproduction of fine detail are such that you happily 'sink into' the picture to discover new detail and new information. One reason is, of course, that they used large negatives that did not have to be enlarged - all they had to do was make contact prints. Another important explanation is the rapid scientific progress of the 1870s and 1880s affecting the mathematical calculation of lenses, combined with new kinds of glass that had higher indexes of refraction and lower dispersion. The most usual term for this kind of lens is double anastigmatic, and well-known brands include the Goerz Dagor and Zeiss Double Protar.

Double anastigmatic lenses could have as many as ten elements cemented together to produce two main groups. This provided a clarity and lack of flare that in many instances made the picture's contrast equal to modern standards, despite the lack of anti-reflection coatings. For anyone using a large format camera it is often of no significance whether the lens is a double anastigmat from the 1890s or a modern multi-coated design.

The great leap forward

Today we do not generally use large format cameras, preferring to use something a lot more convenient. This brings us to the great photographic revolution of our century: the breakthrough of the 35 mm camera in the 1930s. It was a technical leap that meant that you no longer had to carry around big, heavy cameras. With the pioneers of new photography such as Leica and Contax, you could carry your equipment in your pocket! This of course brought enormous demands for improved lens quality, particularly sharpness. Instead of contact printing large format negatives or moderately enlarging medium format negatives, you now had to deal with extreme enlargements while still maintaining definition.

The first person to manage this was physics professor Max Berek, an employee of the Ernst Leitz company in Wetzlar. In the mid-1920s he designed a five-element lens called the Elmax for the newly introduced Leica, which was followed by a four-element version, the now famous Elmar, both of which had three independent lens groups. Using an extensive and elegant series of calculations, Berek succeeded in placing the lens' optical centre unusually far forward. This allowed the diaphragm to be placed between the first and the second groups so that it did not only stop down the lens but also cut down on internal reflections and flare. Both the sharpness and the clarity of this design were so advanced that it is sometimes difficult to notice the difference between pictures taken with the Elmar of the 1930s and those taken with today's lenses. If you have an old Leica with an Elmar lens, don't just keep it in a drawer, load it up with film and learn to enjoy this friendly little device!

Modern performance

The next step in making 35 mm cameras usable was improving the maximum aperture of the lenses. Available films were of low speed, but people still wanted to be able to take photos hand-held, even in low light.

At Carl Zeiss in Jena, a group led by young Dr. Ludwig Bertele worked intensively to equip the new Contax camera with exceptional lenses. Fast lenses required many elements, but the lack of anti-reflection coating made it unattractive to abandon three-group designs, a seemingly insoluble problem. However, Bertele succeeded in producing a seven-element lens with an aperture of f1.5 and with only three groups. At all comparable apertures it was as sharp as the famous Leitz Elmar that had a maximum aperture of f3.5. The amount of manual calculation this required is probably the greatest ever in optical science - later, computers came along and saved the day.

The result of Bertele's incredible feat went on sale in 1932, but as early as 1935 Zeiss solved the problem of anti-reflection coating, rendering much of the work unnecessary. Thereafter they could concentrate on producing lenses with a higher number of groups but with less overall complexity.

In the years leading up to the end of the war in 1945, Zeiss produced several small series of coated lenses. The few who were able to own one were able to enjoy a standard of performance almost as good as we enjoy today.

The diversity of the 1950s

The progress made in the 1920s and 1930s bore fruit in the 1950s. From all the great manufacturers - Voigtländer, Zeiss, Leitz, Nikon and Canon - came a steady stream of cameras and high performance lenses. The growing amateur market had a real choice. Much of the camera equipment produced then still remains in working order today, and it takes a sharp-eyed specialist to notice any difference between pictures taken with a high quality lens from the 1950s, and ones taken with a modern lens. It comes down to small differences in sharpness at large apertures, the saturation of colours, and overall contrast, degrees of difference that rank well below factors such as light conditions and choice of film.

Today's lenses

At the start of the 1960s, optical production was so far advanced that only minor improvements were needed to reach today's standards, at least as far as 'normal' focal lengths and speeds were concerned. There were minor improvement in sharpness at large apertures and in the definition in the outer corners of the image, as well as lower distortion, vignetting, and field curvature. Better colour balance resulted from improved multi-coating techniques. Performance in direct light was also much improved, not just because of multi-coating, but also because of advances in design. Last but not least, advances in production engineering contributed to a reduction in prices. In the early 1950s the price of a Zeiss Sonnar 1.5/50 was the equivalent of two month's salary for a person on average income, whereas today a Zeiss Planar 1.4/50 costs half a month's salary.

It is arguable that this trend ceased in the late 1970s. Normal lenses reached a level of quality that did not need to be improved upon because they already exceeded the capabilities of the available film - and this has remained the case. In this case, no news is good news. Today there are many alternatives to buying brand-new lenses. There is no difference in performance between a new high-quality lens and a high-quality lens made twenty years ago. For normal, everyday photography there is no reason to be obsessive about the latest developments in lenses. The quality of reproduction is good enough even without the latest lenses, and so long as you are not all thumbs you can get great results with old lenses. The picture, after all, is much more about the sharpness of the person standing behind the camera than the sharpness of the lens.

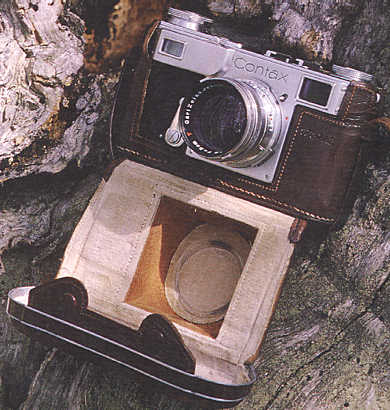

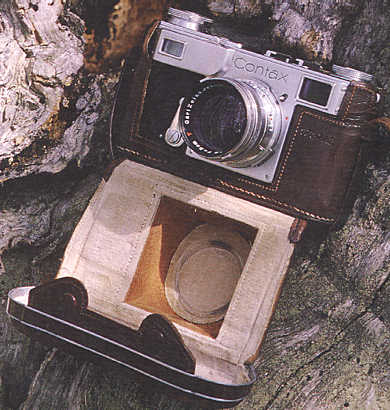

Contax II with anti-reflection treated Sonnar 1.5/50 from the 1930's - the startingpoint for modern optical performance.

By Peter Hennig

Are old lenses as good as new ones? Just how good are older lenses? Can you use old models, or do you have to have the latest to be sure of getting good pictures?

By Peter Hennig If you go out today and buy a cheap camera, it may even come with such refinements as a built-in flash. This is an expensive element in the camera's construction as a proportion of its final, low price, but if you take a closer look at the lens you will see where all the money was saved. The thing that is going to produce the actual picture is a little piece of glass consisting of two lens elements cemented together in front of a very simple shutter. In all essentials it is a Chevalier Achromat of 1835, a design that today can be produced in large quantities for a very low price.

Leica II with Elmar 3.5/50 from the 1930's. A good combination even in 1998.

An 1835 design today

What used to be an annoyingly low maximum aperture can be compensated for by the high-speed films to which we now have access, and other significant optical errors may be lessened by using a curved film path. Anti-reflection coating is not needed for a lens that only consists of a single element, and this again helps keep production costs down. It may come as a bit of a shock that cameras sold today are equipped with lenses of a design that dates back to the early nineteenth century, but in practice the results are perfectly adequate - the pictures serve well enough as unpretentious souvenirs.

As it turns out that the new camera we bought was not as new as we thought, it is worth taking a look at more advanced lens designs of the past to see how well they hold up.

Earlier high quality lenses

When you look at pictures taken at the turn of the century you may often be surprised by the high quality: the sharpness and reproduction of fine detail are such that you happily 'sink into' the picture to discover new detail and new information. One reason is, of course, that they used large negatives that did not have to be enlarged - all they had to do was make contact prints. Another important explanation is the rapid scientific progress of the 1870s and 1880s affecting the mathematical calculation of lenses, combined with new kinds of glass that had higher indexes of refraction and lower dispersion. The most usual term for this kind of lens is double anastigmatic, and well-known brands include the Goerz Dagor and Zeiss Double Protar.

Double anastigmatic lenses could have as many as ten elements cemented together to produce two main groups. This provided a clarity and lack of flare that in many instances made the picture's contrast equal to modern standards, despite the lack of anti-reflection coatings. For anyone using a large format camera it is often of no significance whether the lens is a double anastigmat from the 1890s or a modern multi-coated design.

The great leap forward

Today we do not generally use large format cameras, preferring to use something a lot more convenient. This brings us to the great photographic revolution of our century: the breakthrough of the 35 mm camera in the 1930s. It was a technical leap that meant that you no longer had to carry around big, heavy cameras. With the pioneers of new photography such as Leica and Contax, you could carry your equipment in your pocket! This of course brought enormous demands for improved lens quality, particularly sharpness. Instead of contact printing large format negatives or moderately enlarging medium format negatives, you now had to deal with extreme enlargements while still maintaining definition.

The first person to manage this was physics professor Max Berek, an employee of the Ernst Leitz company in Wetzlar. In the mid-1920s he designed a five-element lens called the Elmax for the newly introduced Leica, which was followed by a four-element version, the now famous Elmar, both of which had three independent lens groups. Using an extensive and elegant series of calculations, Berek succeeded in placing the lens' optical centre unusually far forward. This allowed the diaphragm to be placed between the first and the second groups so that it did not only stop down the lens but also cut down on internal reflections and flare. Both the sharpness and the clarity of this design were so advanced that it is sometimes difficult to notice the difference between pictures taken with the Elmar of the 1930s and those taken with today's lenses. If you have an old Leica with an Elmar lens, don't just keep it in a drawer, load it up with film and learn to enjoy this friendly little device!

Modern performance

The next step in making 35 mm cameras usable was improving the maximum aperture of the lenses. Available films were of low speed, but people still wanted to be able to take photos hand-held, even in low light.

At Carl Zeiss in Jena, a group led by young Dr. Ludwig Bertele worked intensively to equip the new Contax camera with exceptional lenses. Fast lenses required many elements, but the lack of anti-reflection coating made it unattractive to abandon three-group designs, a seemingly insoluble problem. However, Bertele succeeded in producing a seven-element lens with an aperture of f1.5 and with only three groups. At all comparable apertures it was as sharp as the famous Leitz Elmar that had a maximum aperture of f3.5. The amount of manual calculation this required is probably the greatest ever in optical science - later, computers came along and saved the day.

The result of Bertele's incredible feat went on sale in 1932, but as early as 1935 Zeiss solved the problem of anti-reflection coating, rendering much of the work unnecessary. Thereafter they could concentrate on producing lenses with a higher number of groups but with less overall complexity.

In the years leading up to the end of the war in 1945, Zeiss produced several small series of coated lenses. The few who were able to own one were able to enjoy a standard of performance almost as good as we enjoy today.

The diversity of the 1950s

The progress made in the 1920s and 1930s bore fruit in the 1950s. From all the great manufacturers - Voigtländer, Zeiss, Leitz, Nikon and Canon - came a steady stream of cameras and high performance lenses. The growing amateur market had a real choice. Much of the camera equipment produced then still remains in working order today, and it takes a sharp-eyed specialist to notice any difference between pictures taken with a high quality lens from the 1950s, and ones taken with a modern lens. It comes down to small differences in sharpness at large apertures, the saturation of colours, and overall contrast, degrees of difference that rank well below factors such as light conditions and choice of film.

Today's lenses

At the start of the 1960s, optical production was so far advanced that only minor improvements were needed to reach today's standards, at least as far as 'normal' focal lengths and speeds were concerned. There were minor improvement in sharpness at large apertures and in the definition in the outer corners of the image, as well as lower distortion, vignetting, and field curvature. Better colour balance resulted from improved multi-coating techniques. Performance in direct light was also much improved, not just because of multi-coating, but also because of advances in design. Last but not least, advances in production engineering contributed to a reduction in prices. In the early 1950s the price of a Zeiss Sonnar 1.5/50 was the equivalent of two month's salary for a person on average income, whereas today a Zeiss Planar 1.4/50 costs half a month's salary.

It is arguable that this trend ceased in the late 1970s. Normal lenses reached a level of quality that did not need to be improved upon because they already exceeded the capabilities of the available film - and this has remained the case. In this case, no news is good news. Today there are many alternatives to buying brand-new lenses. There is no difference in performance between a new high-quality lens and a high-quality lens made twenty years ago. For normal, everyday photography there is no reason to be obsessive about the latest developments in lenses. The quality of reproduction is good enough even without the latest lenses, and so long as you are not all thumbs you can get great results with old lenses. The picture, after all, is much more about the sharpness of the person standing behind the camera than the sharpness of the lens.

Contax II with anti-reflection treated Sonnar 1.5/50 from the 1930's - the startingpoint for modern optical performance.

Add your message

Login required

Please login here or if you've not registered, you can register here. Registering is safe, quick and free.

Please login here or if you've not registered, you can register here. Registering is safe, quick and free.

photodo Stats

1102 lenses

428 MTF tests

74 in-depth photodo reviews

100+ users join each day

Help the lens community by reviewing or rating a lens today via our lens search

428 MTF tests

74 in-depth photodo reviews

100+ users join each day

Help the lens community by reviewing or rating a lens today via our lens search

Latest Lens Reviews

- Chinon 28mm f/2.8 Vintage Lens Review

- Canon EF 70-200mm f/4L IS II USM Lens Review

- Samyang AF 85mm f/1.4 EF Review

- Sigma 70mm f/2.8 DG Macro Art Review

- Samyang AF 24mm f/2.8 FE Review

- Meike 50mm f/1.7 Review

- Tamron 70-210mm f/4 Di VC USD Review

- Lensbaby Burnside 35mm f/2.8 Review

- Asahi Super Takumar 50mm f/1.4 Review

- Asahi Super-Multi-Coated Takumar 135mm f/3.5 Review